A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him saying, “You are mad, you are not like us.” – St. Anthony

This is, in fact, the theme of every zombie-genre film from 28-Days to I am Legend: a race of people who are sick and who turn on any one who is not sick.

This is, in fact, the theme of every zombie-genre film from 28-Days to I am Legend: a race of people who are sick and who turn on any one who is not sick.

One could unpack many interesting things from Abba Anthony’s comment: thoughts on psychology, the union of soul and body, medicine and Holy Orthodoxy, prophesy and the progress of Death. But there is something there that, at the moment, I find particularly interesting – namely that his comment is also a commentary on deviance and the homogenization of culture.

Clearly, this comment of Abba Anthony’s is not intended as a pleasant thought or a positive outlook on the future. In other words, at its most painfully obvious, he is suggesting that these attacks by the many who are like one another on the one who is dissimilar, are wrong. In other words, for the mass of similar people to feel compelled to attack the one deviant person is itself somehow a form of cultural illness and sign of death. I find that intriguing because, while I think this an exceptionally strong theme in the scriptures and patristic literature, I’ve observed almost no attention being paid to it.

The words of Christ about the value of the one lost lamb, out of place drachma, one threatened sheep, a single pearl, and so on and on are a good starting place. And further, there is his reiteration of the proper attitude toward the stranger (St. Matthew 25) – i.e that the stranger be treated as Christ – that we see Christ in the stranger.

Fundamentally, the stranger is not what we are. In any number of ways. The stranger is the one who is so different that we can’t understand him (strange to us), is the foreigner, the immigrant, the alien, the outsider, the outcast (stranger to us), the deviant, the dissident, abandoned, rejected, neglected, solitary, alienated… he is the man possessed by a demon who lives in the caves – he is the other gender (the woman by the well) – the other religion (Samaritan) and on and on.

In Christ, I see a comprehensive attitude toward all who are, if you will, one-of-a-kind – which, in Orthodox anthropology, is each person. The implication of Christ’s words leave no room for bigotry, homogenization, xenophobia, and on and on. Christ suggests it’s not enough to pray for the unity of all men, but what he describes is action (“ye took me in”) and attitude and spiritual vision (“What ye have done to the least of these, ye have done to me.”)

As Anthony Campolo, a sociologist who has done some study on the subject of deviance, has put it: Christ rejected the ‘accepted people’ – the ‘proper and correct and true’ people. He associated with the deviants – the midget, the tax collector, the sons of thunder, the whore. He said he would bring down the mighty and the lofty, and lift up those of low estate. He means the poor. All of these people – the prisoner, the naked, the sick, the hungry, the thirsty, and the stranger are the poor.

Indeed we are all poor in the eyes of Our Lord, but uniquely so. The entire Economy of Christ’s Incarnation is, in fact, a condescension to lift up those of low estate, to raise the poor with the riches of what they lack. That’s what the Beatitudes are about. When we pray them, we are saying these things. For the deviant, Christ did not suggest that he must be more like everyone else, must fit in, must wish to be more like the crowd – that isn’t what the deviant lacks. What the deviant lacks is the lovingkindness of the crowd. He lacks being treated as the stranger is treated in the Kingdom of God. He lacks being treated as Christ. For St. Anthony, likewise, he does not suggest that the deviant should become like everyone else – quite the contrary. As Christ would say, “Beware when all men speak well of you, for so they treated the false prophets.”

Christ drew crowds, but he was not a man of the crowd. He himself was an outcast, cast out by his own, his brethren, and all men. He was disavowed by his relatives, persecuted by his government, challenged by the leaders of his society, and condemned by his religion. He was abandoned by his own followers, who shortly after announcing him King in Jerusalem, called for Barrabas and abandoned him to the civil authority as a criminal and a heretic. He was fundamentally solitary. Fundamentally deviant. He knows the sorrows of the poor, because he became poor to make us rich, to enrich the impoverished.

Christ became the stranger, and asks that we seek him as we would the lost drachma, lost lamb, threatened sheep, and priceless pearl – and he says that we cannot do this and remain in good standing with the dominant culture. Rather, “if they hated me, they will hate you”, he said, and “the servant is not greater than his master”. He tells us repeatedly that if we wish to find and love him, we must find and love the rest of the poor, and see him there.

The perfect stranger is what? An enemy. An enemy is the ultimate expression of a stranger, as far as any of us is concerned. Whatever he is, he seems to be antithetical to what we are. He negates us, disturbs us, unsettles and upsets us, challenges us, and defies us. He may even be a threat. To this ultimate expression of the stranger, of deviance, of difference from ourselves, Christ say this: “Love your enemy. Bless him even if he curses you. Do good to him, even if he hates you. Pray for him if he despitefully uses you, and if he persecutes you.” Why? What is it that we are winning, in doing this? “That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven, for he maketh the sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sendeth the rain on the just and the unjust.” It’s not natural. It doesn’t feel right. We can’t be expected to do this, not in our culture, at any rate. Exactly. Christ drew the same contrast between the inclination of culture and the call of heaven: “For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? Do not even the publicans do the same? And if ye salute your brethren only, what do ye more than others? Do not even the publicans do so?” Someone says, ‘well, I’m not Christ.’ Perhaps anticipating this, his next words are “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.” And there ended that lesson.

I contend, then, that Christ’s message not only consistently laid out a path of embracing the deviant, but that it is inseparable from his teaching on salvation, and indeed the entire Economy of his Gospel, since he was made the ultimate stranger, the ultimate enemy – he was treated, being the ultimate friend, as the ultimate enemy of mankind, who slew him and cast him out bitterly and with vengeance and glee. Christ really is the ikon of the deviant standing over against the culture, indeed over against the correct, true, and right people even moreso. Crowds followed him, but they left him to show that they were not really of him.

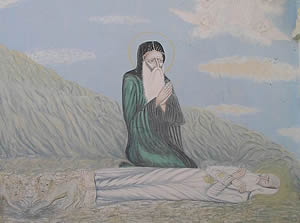

Abba Anthony, likewise, is suggesting that the people of the crowd might, in fact, be mad, even if they all agree with one another. Sanity, prophesies St. Anthony, will ultimately take the form of deviance. Blessed is his wisdom.