The Eschatology of Food

We just finished the Dormition Fast. As one writer said in The Dawn, our Matriarch was on her bed of repose, and so the whole family ceased its celebration and stayed by her side. Theotokos, save, by thy prayers.

We just finished the Dormition Fast. As one writer said in The Dawn, our Matriarch was on her bed of repose, and so the whole family ceased its celebration and stayed by her side. Theotokos, save, by thy prayers.

I’m interested in the eschatological aspects of fasting. I see fasting, and the life of the monks, who don’t touch meat, as a foretelling of the end of Death. What the quasi-Darwinists hold is what we Orthodox must reject (you don’t have to “believe in evolution” to accept the basic assumptions of the Darwinists) – namely, that Death is natural – that it’s a normal condition of the natural order. We repudiate this. There is no middle ground. Death is an attack on man and the created order. It has entered the natural order as an invader, and is therefore a negation of the normal (nor do we confuse, conflate, and substitute the concepts of “natural” with “normal” as do the Darwinists).

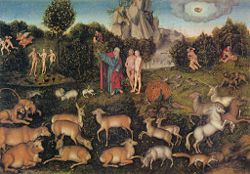

And so our eating of meat is made possible only through Death, a thing which is passing away, a thing over which we live to triumph and die to defeat. When we fast from flesh, just as the monks always do, those who go before us on the path, we recall that “every green thing” was given to us in Eden, but that we are no longer the veegans we were – because of Death, and we foretell the fulfillment of the Kingdom, in which the “lion will lie down with the lamb, and a little child will lead them” and neither will there be any more Death or sorrow. We look to a heaven in which the enmity between creatures is replaced with the reign of peace. The alienation, the fragmentation, that is Death itself, is replaced with life that destroys Death.

So often, the cultural religious response is suspicious of Veeganism and Vegetarianism, and reaches quickly for heterodox hermeutics and the first council in the New Testament, in which nothing is forbidden to eat except strangled things and blood and (elsewhere), in the advice of the Apostle, things sacrificed to idols. But this is to miss the point, and indeed to Protestantize our thinking, using one point over against another, as though ours is a religion of proof texts and a debate over contradictions – a faith in this not that – either/or rather than both/and.

It’s like talking about fasting at all: “Are you judging your brother? Are you prideful about your fasting? Love is more important than fasting.” One cannot answer these attitudes, because they’re formulated on a Protestant mentality in the first place. A religious psychology predicated on hashing out dialectical conflicts. When one even begins to question our consumption of meat, the immense suffering – both human and animal – brought about my the meat processing industry, etc. – it’s immediately treated as suspect. So be it. But the Orthodox response is ultimately a destruction of death and, yes, a taking away of that hamburger and that pepperoni pizza. What is permitted during the feasts is with equal truth and fervor forbidden during the fasts, and moreso will be extinguished and nonexistent in the fulness of the Kingdom. If we cannot take full stock of that truth, the problem is in our own prejudices, and not in the Faith or in those who articulate it. The Incarnation itself is null without the end of Death, so it is the very Faith itself that is vain if this is not true.

No, we don’t go around pointing fingers, but neither is it necessarily an expression of pride, arrogance, or judgment to be veegan – and to be veegan precisely as a piety – as a devotion – as an expression of Faith. “Keep quiet about it, then,” we are told. No. The same people who say this are busy writing articles on all kinds of topics – how can they say this one is forbidden, and on what basis? On the contrary, if we can’t have a free and open discussion on it, then perhaps that very religious psychology – the very “piety” being suggested – is itself an even more important topic for conversation, and this issue is just a catalyst, a useful example, for bringing it to light.

No, we don’t go around pointing fingers, but neither is it necessarily an expression of pride, arrogance, or judgment to be veegan – and to be veegan precisely as a piety – as a devotion – as an expression of Faith. “Keep quiet about it, then,” we are told. No. The same people who say this are busy writing articles on all kinds of topics – how can they say this one is forbidden, and on what basis? On the contrary, if we can’t have a free and open discussion on it, then perhaps that very religious psychology – the very “piety” being suggested – is itself an even more important topic for conversation, and this issue is just a catalyst, a useful example, for bringing it to light.

Anthony Campolo once said, “My theology is best expressed in elevators.” By which he meant that, contrary to the demands and assumptions of the dominant social order, he wouldn’t turn, and he would also sing on elevators, which you’re not supposed to do (people don’t get on, when the doors open). This kind of mundane warfare with the world is simply the every day expression of our all out campaign against the world system – the ascendant societal framework. It’s the Ghandi-esque expression of small, continual acts of repudiation, rejection, and rebellion in the face of an all-consuming overriding social system. It is the brief ignition of joy in the darkness of the way things supposedly are.

In the same way, I like to challenge the social order’s assumptions about meat, in small continual doses. I live in a part of the country in which it’s just not considered a meal w/o copious portions of carcass. Vegetables are, at best, a garnish. Animal products constitute the primary fare, and ridicule of vegetarians and religious vehemence about “liberty in Christ” and privacy in fasting (which means, typically, not fasting at all), is generally a cover for decadent gluttony – the kind of gluttony that causes immense health problems, not to mention pain and discomfort waddling away from the table (irrational, almost insane gluttony). I’m a flexitarian – which means sometimes I’m veegan, sometimes vegetarian, and sometimes I eat hamburgers – it’s a long story, but it’s part of an ongoing process. Often, I’ll order toast and eggs at local diners. I almost always get a bewildered query from the waitress, “No meat?!?” And I always have the same response: “Eggs *are* meat.” Usually I get a moment of hesitation and thought and a “Hmm. Guess so.”, but it can range anywhere from a hrrmph to laughter. The point is that we need to question the assumptions we’ve absorbed with our mother’s milk and taken from the very air of the world into which we were born. And one of those key assumptions is that Death is a given – it’s a normal, natural, native part of the created order – and our lives aren’t complete without depending on the death of others. There are implications for attitudes about war, capital punishment, abortion, and what have you. Food is just an entry point.

The thing is, being afraid to talk about it, or ask these questions, or keep the topic open, or think about it – think through the implications of our doctrines, and our relation to the assumptions embedded in the culture’s behavior, attitudes, and ideas, is itself a non-Christian attitude. An anti-Christian one, in fact. And if we can’t do it about food, we can’t effectively do it about money, about human relationships, about work, or about any other significant area of human endeavour. Food is a crucible issue for us, which is one of the reasons we fast. It’s that important, it’s a capsulized representation of our religious attitudes about creation, the world, the Incarnation, and all else that we consider a matter of Orthodox interest.

So frankly, here’s talking about it.