From the archives of the Seraphim Society

Contents

- Life of St. Seraphim

- Troparion & Kontakion

- More Resources

Commemorated on January 2

From www.oca.org

The Life of St. Seraphim

Saint Seraphim of Sarov, a great ascetic of the Russian Church, was born on July 19, 1754. His parents, Isidore and Agathia Moshnin, were inhabitants of Kursk. Isidore was a merchant. Toward the end of his life, he began construction of a cathedral in Kursk, but he died before the completion of the work. His little son Prochorus,the future Seraphim, remained in the care of his widowed mother, who raised her son in piety.

After the death of her husband, Agathia Moshnina continued with the construction of the cathedral. Once she took the seven-year-old Prochorus there with her, and he fell from the scaffolding around the seven-storey bell tower. He should have been killed, but the Lord preserved the life of the future luminary of the Church. The terrified mother ran to him and found her son unharmed.

Young Prochorus, endowed with an excellent memory, soon mastered reading and writing. From his childhood he loved to attend church services, and to read both the Holy Scripture and the Lives of the Saints with his fellow students. Most of all, he loved to pray or to read the Holy Gospel in private.

At one point Prochorus fell grievously ill, and his life was in danger. In a dream the boy saw the Mother of God, promising to visit and heal him. Soon past the courtyard of the Moshnin home came a church procession with the Kursk Root Icon of the Sign (November 27). His mother carried Prochorus in her arms, and he kissed the holy icon, after which he speedily recovered.

While still in his youth Prochorus made his plans to devote his life entirely to God and to go to a monastery. His devout mother did not object to this and she blessed him on his monastic path with a copper cross, which he wore on his chest for the rest of his life. Prochorus set off on foot with pilgrims going from Kursk to Kiev to venerate the Saints of the Caves.

The Elder Dositheus (actually a woman, Daria Tyapkina), whom Prochorus visited, blessed him to go to the Sarov wilderness monastery, and there seek his salvation. Returning briefly to his parental home, Prohkor bid a final farewell to his mother and family. On November 20, 1778 he arrived at Sarov, where the monastery then was headed by a wise Elder, Father Pachomius. He accepted him and put him under the spiritual guidance of the Elder Joseph. Under his direction Prochorus passed through many obediences at the monastery: he was the Elder’s cell-attendant, he toiled at making bread and prosphora, and at carpentry. He fulfilled all his obediences with zeal and fervor, as though serving the Lord Himself. By constant work he guarded himself against despondency (accidie), this being, as he later said, “the most dangerous temptation for new monks. It is treated by prayer, by abstaining from idle chatter, by strenuous work, by reading the Word of God and by patience, since it is engendered by pettiness of soul, negligence, and idle talk.”

With the blessing of Igumen Pachomius, Prochorus abstained from all food on Wednesdays and Fridays, and went into the forest, where in complete isolation he practiced the Jesus Prayer. After two years as a novice, Prochorus fell ill with dropsy, his body became swollen, and he was beset with suffering. His instructor Father Joseph and the other Elders were fond of Prochorus, and they provided him care. The illness dragged on for about three years, and not once did anyone hear from him a word of complaint. The Elders, fearing for his very life, wanted to call a doctor for him, but Prochorus asked that this not be done, saying to Father Pachomius: “I have entrusted myself, holy Father, to the True Physician of soul and body, our Lord Jesus Christ and His All-Pure Mother.”

He asked that a Molieben be offered for his health. While the others were praying in church, Prochorus had a vision. The Mother of God appeared to him accompanied by the holy Apostles Peter and John the Theologian. Pointing with Her hand towards the sick monk, the Most Holy Virgin said to St John, “He is one of our kind.” Then She touched the side of the sick man with Her staff, and immediately the fluid that had swelled up his body began to flow through the incision that She made. After the Molieben, the brethren found that Prochorus had been healed, and only a scar remained as evidence of the miracle.

Soon, at the place of the appearance of the Mother of God, an infirmary church was built for the sick. One of the side chapels was dedicated to Sts Zosimas and Sabbatius of Solovki (April 17). With his own hands, St Seraphim made an altar table for the chapel out of cypress wood, and he always received the Holy Mysteries in this church.

After eight years as a novice at the Sarov monastery, Prochorus was tonsured with the name Seraphim, a name reflecting his fiery love for the Lord and his zealous desire to serve Him. After a year, Seraphim was ordained as hierodeacon.

Earnest in spirit, he served in the temple each day, incessantly praying even after the service. The Lord granted him visions during the church services: he often saw holy angels serving with the priests. During the Divine Liturgy on Great and Holy Thursday, which was celebrated by the igumen Father Pachomius and by Father Joseph, St Seraphim had another vision. After the Little Entrance with the Gospel, the hierodeacon Seraphim pronounced the words “O Lord, save the God-fearing, and hear us.” Then, he lifted his orarion saying, “And unto ages of ages.” Suddenly, he was blinded by a bright ray of light.

Looking up, St Seraphim beheld the Lord Jesus Christ, coming through the western doors of the temple, surrounded by the Bodiless Powers of Heaven. Reaching the ambo, the Lord blessed all those praying and entered into His Icon to the right of the royal doors. St Seraphim, in spiritual rapture after this miraculous vision, was unable to utter a word, nor to move from the spot. They led him by the hand into the altar, where he just stood for another three hours, his face having changed color from the great grace that shone upon him. After the vision the saint intensified his efforts. He toiled at the monastery by day, and he spent his nights praying in his forest cell.

In 1793, Hierodeacon Seraphim was ordained to the priesthood, and he served the Divine Liturgy every day. After the death of the igumen Father Pachomius, St Seraphim received the blessing of the new Superior Father Isaiah, to live alone in a remote part of the forest three and a half miles from the monastery. He named his new home “Mount Athos,” and devoted himself to solitary prayer. He went to the monastery only on Saturday before the all-night Vigil, and returned to his forest cell after Sunday’s Liturgy, at which he partook of the Divine Mysteries.

Fr Seraphim spent his time in ascetical struggles. His cell rule of prayer was based on the rule of St Pachomius for the ancient desert monasteries. He always carried the Holy Gospels with him, reading the entire New Testament in the course of a week. He also read the holy Fathers and the service books. The saint learned many of the Church hymns by heart, and sang them while working in the forest. Around his cell he cultivated a garden and set up a beehive. He kept a very strict fast, eating only once during the entire day, and on Wednesdays and Fridays he completely abstained from food. On the first Sunday of the Great Fast he did not partake of food at all until Saturday, when he received the Holy Mysteries.

The holy Elder was sometimes so absorbed by the unceasing prayer of the heart that he remained without stirring, neither hearing nor seeing anything around him. The schemamonk Mark the Silent and the hierodeacon Alexander, also wilderness-dwellers, would visit him every now and then. Finding the saint immersed in prayer, they would leave quietly, so they would not disturb his contemplation.

In the heat of summer the righteous one gathered moss from a swamp as fertilizer for his garden. Gnats and mosquitoes bit him relentlessly, but he endured this saying, “The passions are destroyed by suffering and by afflictions.”

His solitude was often disturbed by visits from monks and laymen, who sought his advice and blessing. With the blessing of the igumen, Fr Seraphim prohibited women from visiting him, then receiving a sign that the Lord approved of his desire for complete silence, he banned all visitors. Through the prayers of the saint, the pathway to his wilderness cell was blocked by huge branches blown down from ancient pine trees. Now only the birds and the wild beasts visited him, and he dwelt with them as Adam did in Paradise. They came at midnight and waited for him to complete his Rule of prayer. Then he would feed bears, lynxes, foxes, rabbits, and even wolves with bread from his hand. St Seraphim also had a bear which would obey him and run errands for him.

In order to repulse the onslaughts of the Enemy, St Seraphim intensified his toil and began a new ascetical struggle in imitation of St Simeon the Stylite (September 1). Each night he climbed up on an immense rock in the forest, or a smaller one in his cell, resting only for short periods. He stood or knelt, praying with upraised hands, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” He prayed this way for 1,000 days and nights.

Three robbers in search of money or valuables once came upon him while he was working in his garden. The robbers demanded money from him. Though he had an axe in his hands, and could have put up a fight, but he did not want to do this, recalling the words of the Lord: “Those who take up the sword will perish by the sword” (Mt. 26: 52). Dropping his axe to the ground, he said, “Do what you intend.” The robbers beat him severely and left him for dead. They wanted to throw him in the river, but first they searched the cell for money. They tore the place apart, but found nothing but icons and a few potatoes, so they left. The monk, regained consciousness, crawled to his cell, and lay there all night.

In the morning he reached the monastery with great difficulty. The brethren were horrified, seeing the ascetic with several wounds to his head, chest, ribs and back. For eight days he lay there suffering from his wounds. Doctors called to treat him were amazed that he was still alive after such a beating.

Fr Seraphim was not cured by any earthly physician: the Queen of Heaven appeared to him in a vision with the Apostles Peter and John. Touching the saint’s head, the Most Holy Virgin healed him. However, he was unable to straighten up, and for the rest of his life he had to walk bent over with the aid of a stick or a small axe. St Seraphim had to spend about five months at the monastery, and then he returned to the forest. He forgave his abusers and asked that they not be punished.

In 1807 the abbot, Father Isaiah, fell asleep in the Lord. St Seraphim was asked to take his place, but he declined. He lived in silence for three years, completely cut off from the world except for the monk who came once a week to bring him food. If the saint encountered a man in the forest, he fell face down and did not get up until the passerby had moved on. St Seraphim acquired peace of soul and joy in the Holy Spirit. The great ascetic once said, “Acquire the spirit of peace, and a thousand souls will be saved around you.”

The new Superior of the monastery, Father Niphon, and the older brethren of the monastery told Father Seraphim either to come to the monastery on Sundays for divine services as before, or to move back into the monastery. He chose the latter course, since it had become too difficult for him to walk from his forest cell to the monastery. In the spring of 1810, he returned to the monastery after fifteen years of living in the wilderness.

Continuing his silence, he shut himself up in his cell, occupying himself with prayer and reading. He was also permitted to eat meals and to receive Communion in his cell. There St Seraphim attained the height of spiritual purity and was granted special gifts of grace by God: clairvoyance and wonderworking. After five years of solitude, he opened his door and allowed the monks to enter. He continued his silence, however, teaching them only by example.

On November 25, 1825 the Mother of God, accompanied by the two holy hierarchs commemorated on that day (Hieromartyr Clement of Rome, and St Peter, Archbishop of Alexandria), appeared to the Elder in a vision and told him to end his seclusion and to devote himself to others. He received the igumen’s blessing to divide his time between life in the forest, and at the monastery. He did not return to his Far Hermitage, but went to a cell closer to the monastery. This he called his Near Hermitage. At that time, he opened the doors of his cell to pilgrims as well as his fellow-monks.

The Elder saw into the hearts of people, and as a spiritual physician, he healed their infirmities of soul and body through prayer and by his grace-filled words. Those coming to St Seraphim felt his great love and tenderness. No matter what time of the year it was, he would greet everyone with the words, “Christ is Risen, my joy!” He especially loved children. Once, a young girl said to her friends, “Father Seraphim only looks like an old man. He is really a child like us.”

The Elder was often seen leaning on his stick and carrying a knapsack filled with stones. When asked why he did this, the saint humbly replied,”I am troubling him who troubles me.”

In the final period of his earthly life St Seraphim devoted himself to his spiritual children, the Diveyevo women’s monastery. While still a hierodeacon he had accompanied the late Father Pachomius to the Diveyevo community to its monastic leader, Mother Alexandra, a great woman ascetic, and then Father Pachomius blessed St Seraphim to care always for the “Diveyevo orphans.” He was a genuine father for the sisters, who turned to him with all their spiritual and material difficulties.

St Seraphim also devoted much effort to the women’s monastic community at Diveyevo. He himself said that he gave them no instructions of his own, but it was the Queen of Heaven who guided him in matters pertaining to the monastery. His disciples and spiritual friends helped the saint to feed and nourish the Diveyevo community. Michael V. Manturov, healed by the monk from grievous illness, was one of Diveyvo’s benefactors. On the advice of the Elder he took upon himself the exploit of voluntary poverty. Elena Vasilievna Manturova, one of the Diveyevo sisters, out of obedience to the Elder, voluntarily consented to die in place of her brother, who was still needed in this life.

Nicholas Alexandrovich Motovilov, was also healed by the monk. In 1903, shortly before the glorification of the saint, the remarkable “Conversation of St Seraphim of Sarov with N. A. Motovilov” was found and printed. Written by Motovilov after their conversation at the end of November 1831, the manuscript was hidden in an attic in a heap of rubbish for almost seventy years. It was found by the author S. A. Nilus, who was looking for information about St Seraphim’s life. This conversation is a very precious contribution to the spiritual literature of the Orthodox Church. It grew out of Nicholas Motovilov’s desire to know the aim of the Christian life. It was revealed to St Seraphim that Motovilov had been seeking an answer to this question since childhood, without receiving a satisfactory answer. The holy Elder told him that the aim of the Christian life is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit, and went on to explain the great benefits of prayer and the acquisition of the Holy Spirit.

Motovilov asked the saint how we can know if the Holy Spirit is with us or not. St Seraphim spoke at length about how people come to be in the Spirit of God, and how we can recognize His presence in us, but Motovilov wanted to understand this better. Then Father Seraphim took him by the shoulders and said, “We are both in the Spirit of God now, my son. Why don’t you look at me?”

Motovilov replied, “I cannot look, Father, for your eyes are flashing like lightning, and your face is brighter than the sun.”

St Seraphim told him, “Don’t be alarmed, friend of God. Now you yourself have become as bright as I am. You are in the fulness of the Spirit of God yourself, otherwise you would not be able to see me like this.”

Then St Seraphim promised Motovilov that God would allow him to retain this experience in his memory all his life. “It is not given for you alone to understand,” he said, “but through you it is for the whole world.”

Everyone knew and esteemed St Seraphim as a great ascetic and wonderworker. A year and ten months before his end, on the Feast of the Annunciation, St Seraphim was granted to behold the Queen of Heaven once more in the company of St John the Baptist, the Apostle John the Theologian and twelve Virgin Martyrs (Sts Barbara, Katherine, Thekla, Marina, Irene, Eupraxia, Pelagia, Dorothea, Makrina, Justina, Juliana, and Anysia). The Most Holy Virgin conversed at length with the monk, entrusting the Diveyevo sisters to him. Concluding the conversation, She said to him: “Soon, My dear one, you shall be with us.” The Diveyevo nun Eupraxia was present during this visit of the Mother of God, because the saint had invited her.

In the last year of St Seraphim’s life, one of those healed by him saw him standing in the air during prayer. The saint strictly forbade this to be mentioned until after his death.

St Seraphim became noticeably weaker and he spoke much about his approaching end. During this time they often saw him sitting by his coffin, which he had placed in the ante-room of his cell, and which he had prepared for himself.

The saint himself had marked the place where finally they would bury him, near the altar of the Dormition cathedral. On January 1, 1833 Father Seraphim came to the church of Sts Zosimas and Sabbatius one last time for Liturgy and he received the Holy Mysteries, after which he blessed the brethren and bid them farewell, saying: “Save your souls. Do not be despondent, but watchful. Today crowns are being prepared for us.”

On January 2, Father Paul, the saint’s cell-attendant, left his own cell at six in the morning to attend the early Liturgy. He noticed the smell of smoke coming from the Elder’s cell. St Seraphim would often leave candles burning in his cell, and Father Paul was concerned that they could start a fire.

“While I am alive,” he once said, “there will be no fire, but when I die, my death shall be revealed by a fire.” When they opened the door, it appeared that books and other things were smoldering. St Seraphim was found kneeling before an icon of the Mother of God with his arms crossed on his chest. His pure soul was taken by the angels at the time of prayer, and had flown off to the Throne of the Almighty God, Whose faithful servant St Seraphim had been all his life.

St Seraphim has promised to intercede for those who remember his parents, Isidore and Agathia.

Troparion – Tone 4

You loved Christ from your youth, O blessed one,

and longing to work for Him alone you struggled in the wilderness in constant prayer and labor.

With penitent heart and great love for Christ you were favored by the Mother of God.

Therefore we cry to you:

“Save us by your prayers, venerable Seraphim, our father.”

Kontakion – Tone 2

Forsaking the beauty as well as the corruption of this world,

you settled in the monastery of Sarov, O Saint.

There you lived an angelic life,

becoming for many the way to salvation.

Therefore, Christ has glorified you, Father Seraphim,

enriching you with abundant healing and miracles.

So we cry to you: “Save us by your prayers, venerable Seraphim, our father.”

More Resources:

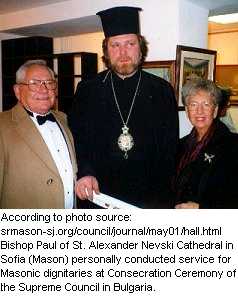

It occasionally bears repeating, that Orthodox are forbidden to be freemasons. Period. No, ifs, ands, buts. Not if we understand it in a certain way. Not if it is this or isn’t that. It’s verboten. Among the various acts condemning participation in masonry are:

It occasionally bears repeating, that Orthodox are forbidden to be freemasons. Period. No, ifs, ands, buts. Not if we understand it in a certain way. Not if it is this or isn’t that. It’s verboten. Among the various acts condemning participation in masonry are: August Rush is a film about the connection that love creates between human beings. Orson Scott Card’s science fiction describes this as “philotic” strands that join anyone in the universe that is involved in someone else’s life. His primary character Ender, in that now classic series, says (to paraphrase) “I think once you know someone, know what they want and need, even an enemy, it is impossible not to love him.” August Rush is art about strands as frail as hope. It’s about want and need, and the quest for meaning in individual lives. All men seek meaning, and it is always there for us, if we take it. The film is a kind of Pilgrims Progress, as well, that reminds us we might spend years walking down a path of forgetfulness, not even thinking of the path less taken.

August Rush is a film about the connection that love creates between human beings. Orson Scott Card’s science fiction describes this as “philotic” strands that join anyone in the universe that is involved in someone else’s life. His primary character Ender, in that now classic series, says (to paraphrase) “I think once you know someone, know what they want and need, even an enemy, it is impossible not to love him.” August Rush is art about strands as frail as hope. It’s about want and need, and the quest for meaning in individual lives. All men seek meaning, and it is always there for us, if we take it. The film is a kind of Pilgrims Progress, as well, that reminds us we might spend years walking down a path of forgetfulness, not even thinking of the path less taken. He who digs a pit falls into it. Numerous Orthodox writers have been correct to challenge the assumptions of Augustinism and to format a critique of Western religion and culture on that basis. However, when this is done as an intellectual fetish, a titillating hobby, or a dilettante’s alternative to pursuing the deification for which St. Augustine is remembered with such reverence by St. Photius and others, it is too easy to fall into the very errors attributed to St. Augustine.

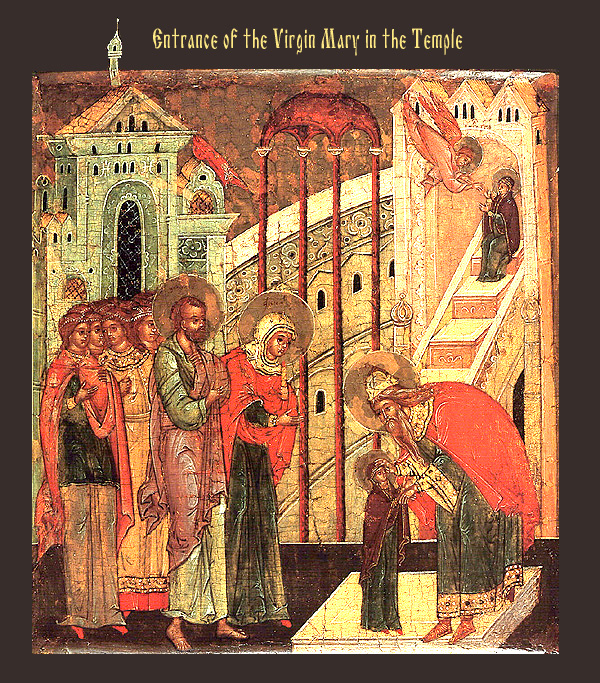

He who digs a pit falls into it. Numerous Orthodox writers have been correct to challenge the assumptions of Augustinism and to format a critique of Western religion and culture on that basis. However, when this is done as an intellectual fetish, a titillating hobby, or a dilettante’s alternative to pursuing the deification for which St. Augustine is remembered with such reverence by St. Photius and others, it is too easy to fall into the very errors attributed to St. Augustine. This is the day of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple.Fulfilling their vow to God, Sts. Joachim and Anna, her holy parents, presented Mary at three years old at the temple, where she would live as virgin for nine years, until her Betrothal to St. Joseph. The High Priest Zacharias blessed her with these words: “The Lord has glorified thy name in every generation; it is in thee that He will reveal the Redemption that he has prepared for his people in the last days.” He then led her into the Holy of Holies, where the High Priest alone may enter, and only once a year on the Day of Atonement.

This is the day of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple.Fulfilling their vow to God, Sts. Joachim and Anna, her holy parents, presented Mary at three years old at the temple, where she would live as virgin for nine years, until her Betrothal to St. Joseph. The High Priest Zacharias blessed her with these words: “The Lord has glorified thy name in every generation; it is in thee that He will reveal the Redemption that he has prepared for his people in the last days.” He then led her into the Holy of Holies, where the High Priest alone may enter, and only once a year on the Day of Atonement. It is my thinking that the US represents the global political system of the apocalypse, with its tendrils or heads as Israel, Turkey, the UK, and the states of Western Europe, and having a body of lesser heads, including its client states. I also think that a globally united Christianity will be made of Orthodox Churches, Rome, and Protestant groups, and that this new entity will be an apostasy, and will seek then, having united ‘all Christians’, to unite all Faiths in some fashion, in a kind of temple of all Faith, though we can scarcely conceive of such a practical possibility now. I think, finally, that a new global economic system will be proposed and followed, as the savior of the global market. I think these things will combine into a kind of new babel, as a unified effort of man. I think these things are preceded by terrible natural disasters, which I think in the classic pattern of judgment includes climate change as a result of man’s sinful behavior, and a campaign of perpetual warfare. I think they will be succeeded by the apocalypse. …

It is my thinking that the US represents the global political system of the apocalypse, with its tendrils or heads as Israel, Turkey, the UK, and the states of Western Europe, and having a body of lesser heads, including its client states. I also think that a globally united Christianity will be made of Orthodox Churches, Rome, and Protestant groups, and that this new entity will be an apostasy, and will seek then, having united ‘all Christians’, to unite all Faiths in some fashion, in a kind of temple of all Faith, though we can scarcely conceive of such a practical possibility now. I think, finally, that a new global economic system will be proposed and followed, as the savior of the global market. I think these things will combine into a kind of new babel, as a unified effort of man. I think these things are preceded by terrible natural disasters, which I think in the classic pattern of judgment includes climate change as a result of man’s sinful behavior, and a campaign of perpetual warfare. I think they will be succeeded by the apocalypse. …